Seema Aziz is the co-founder and managing director of textile company Sefam. In 1988 she founded CARE Foundation to build schools and provide quality education to underprivileged children in Pakistan. From the first school built in 1991, CARE now oversees the education of 300,000 children in 888 schools across Pakistan thanks to its innovative Adopt a School program. CAPS spoke to Seema to find out what motivates her strong commitment to improving educational outcomes for Pakistan’s youth.

CAPS: Thank you for taking the time to speak with us today. Your story is a truly remarkable story, from starting a successful textile company to founding Pakistan’s largest educational NGO. Can you take us back to the beginning and share how you become involved with community development?

Seema: It started with the business. The first shop opened its doors in 1985. We worked really hard for a whole year: running around, fixing the quality of the fabric and dyes. We put together whatever little bits of money we had and put all of our energy into the business. Soon we built a reputation for our locally made, high-quality fabrics.

The belief that we, as humans, have a responsibility to others as part of civil society was always a part of our company’s values. In 1988 there was a terrible flood in Lahore and we realized we had to help the people affected. So we went out to deliver food and medicine.

After the water receded, many people had lost their homes and there were thousands camped out on the roads. And much more help was needed. Our first idea was to help people to rebuild homes. We thought we could do ten homes. We picked ten people at random from the hundreds who applied and gave them the money to rebuild. Then we repeated the process a few times and ended up building about 80 homes.

CAPS: How did that evolve into a focus on education?

Seema: I was particularly involved in one area that was hit badly: no electricity, no sewage system and no running water. As I was going around to check on people, hundreds of children would follow me. I asked some of the women there why they were following me and they replied, “What else should they do? There’s no school.” That really horrified me. I said to them, “What if I build a school?” They were all so excited. They told me to stop building the homes and to build the school.

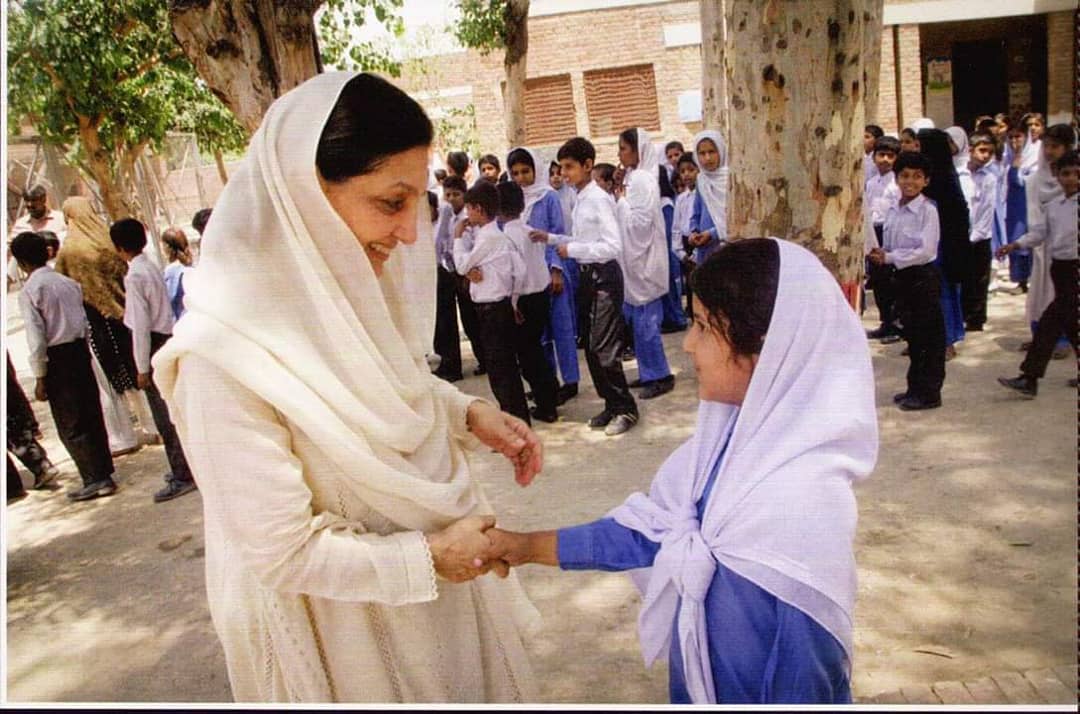

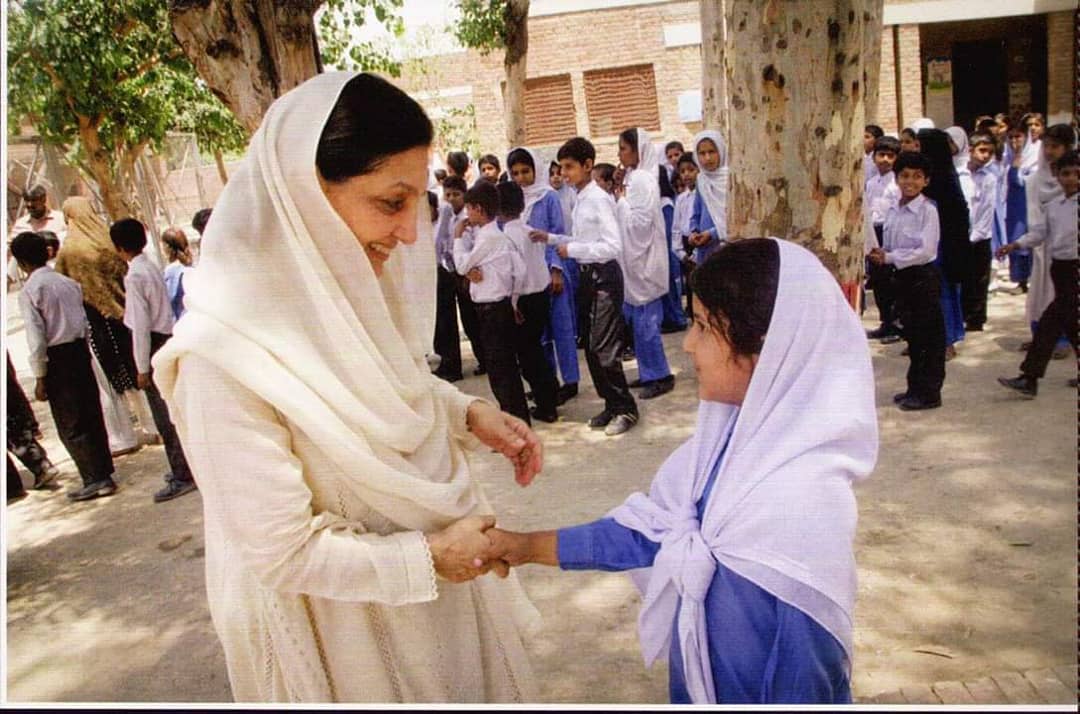

My friends and family in the city told me I was totally mad, that the poor don’t want to educate their children. But when I looked at the people I was trying to help, I realized the only difference between them and me was an education. Thanks to my education I had so many opportunities. Those mothers wanted a better life for their children the same as any mothers do. If the opportunity does not exist, it’s not their fault, it’s the fault of society. I decided to build a school. We collected donations from friends and family and in 1991, we opened the doors. On the day of opening 250 children were standing outside. They had all lined up for a chance at a better life.

CAPS: Apart from the physical buildings, what else went into developing the schools?

Seema: Developing the curriculum was important. When I looked at what the government schools were teaching, I realized that it wasn’t enough. That’s why we introduced the English curriculum. And we also had to provide pencils and books and other necessary supplies for the children.

I didn’t want any child to ever grow up thinking that the support we were giving them was charity, because it wasn’t. It’s their right and our duty to ensure that they get that education. And so, they each paid ten rupees for their education, then everything else was free.

By the end of the first year, word had gotten around that ours was a school where education happens. The next year we had 450 children, then 850 the year after. We acquired some more land, so we built another school and then another. And the children worked so hard, they learned everything we taught them.

CAPS: How did the partnership with the government come about?

Seema: By 1998, I was realizing the sheer number of children in need. And in my heart, I knew that only government could provide education for all. No private organization could ever provide education for all, it needed government infrastructure. That same year, the government asked me to go and survey about 25 schools in Lahore. I was horrified: no running water, no toilets, no lights, no furniture, no teachers, and children sitting on broken floors in their neat little uniforms waiting for an education, which was never going to happen. I saw in my city of Lahore, which we think of as the cultural heart of Pakistan, schools with no roofs, schools with no door.

I told the government that we would partner with them to support ten schools. CARE would take on complete responsibility for the school’s operations and expenses (capital and running), including the infrastructural improvements, staff recruitment, training and salary. We adopted government schools that were not in good shape, and by the end of the year we turned them around. Enrolments doubled and then quadrupled.

CAPS: What have been the major challenges CARE has faced?

Seema: Originally when we took over the government schools, we said that we would stay for ten years. We would help train others, then slowly reduce the number of our people. But it hasn’t worked out like that. We still haven’t exited those schools because we know the moment we walk out, they’ll collapse. They keep asking us to take on more schools, but getting money from the government has also been difficult. So, I’ve committed a percentage of my company’s earnings to CARE.

Another challenge is the drop-out rate, especially among girls. There are many bright students who do not have the means to go to college. So, we set up a scholarship program that supports our students to go to some of the best colleges in the country.

CAPS: What keeps you motivated to keep CARE running despite these challenges?

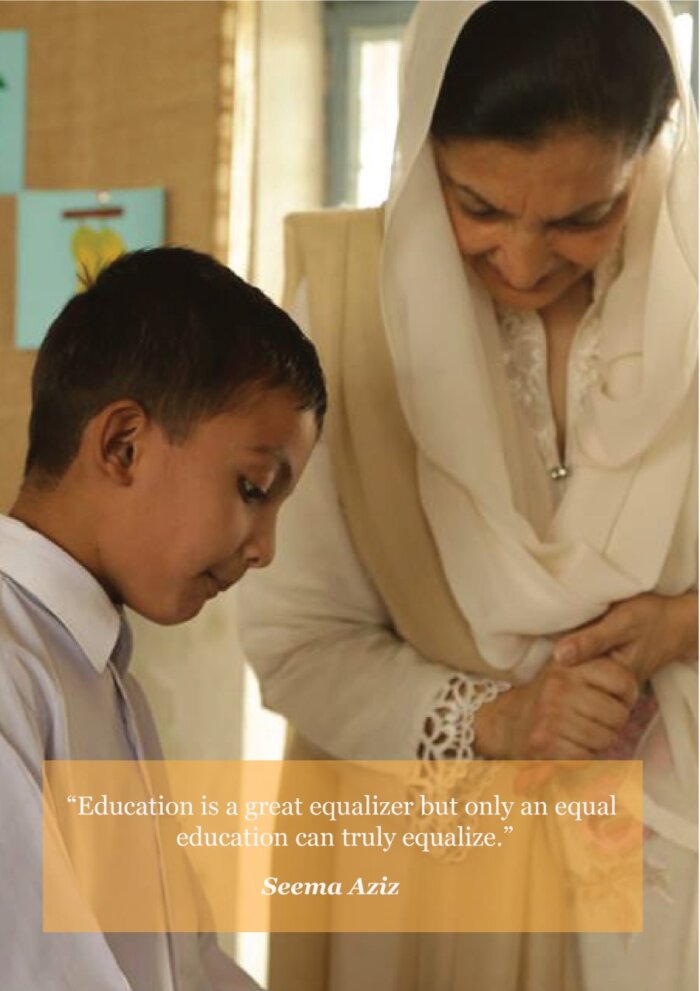

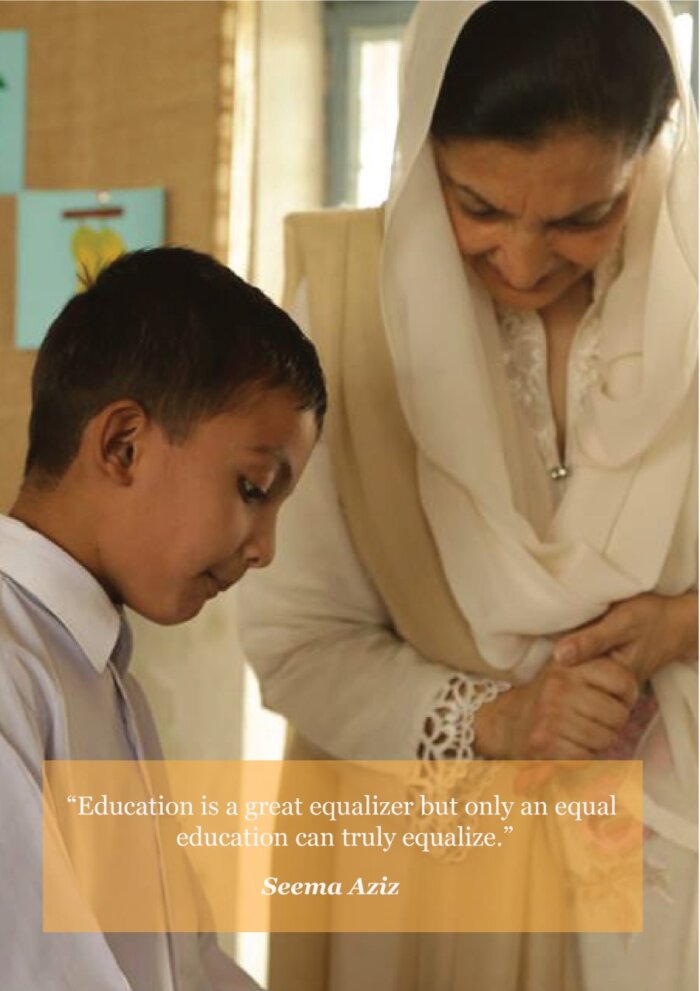

Seema: We are totally committed to children graduating. Education is a great equalizer. It shouldn’t just be available to rich children. We need to even the playing field and create equal opportunities. We really believe in that, and we’ve done our best. I think that’s the main thing.