The benefits of the digital age extend to the social sector, but how can we ensure equitable access? Across Asia, digital technology has enabled greater connectivity and flow of information and resources. The social sector has largely benefited from this shift, drawing on digital tools and platforms to increase effectiveness, expand access to social support services, and supercharge fundraising efforts. Continue reading here.

Realizing the promise of digital technology for Asia’s social sector

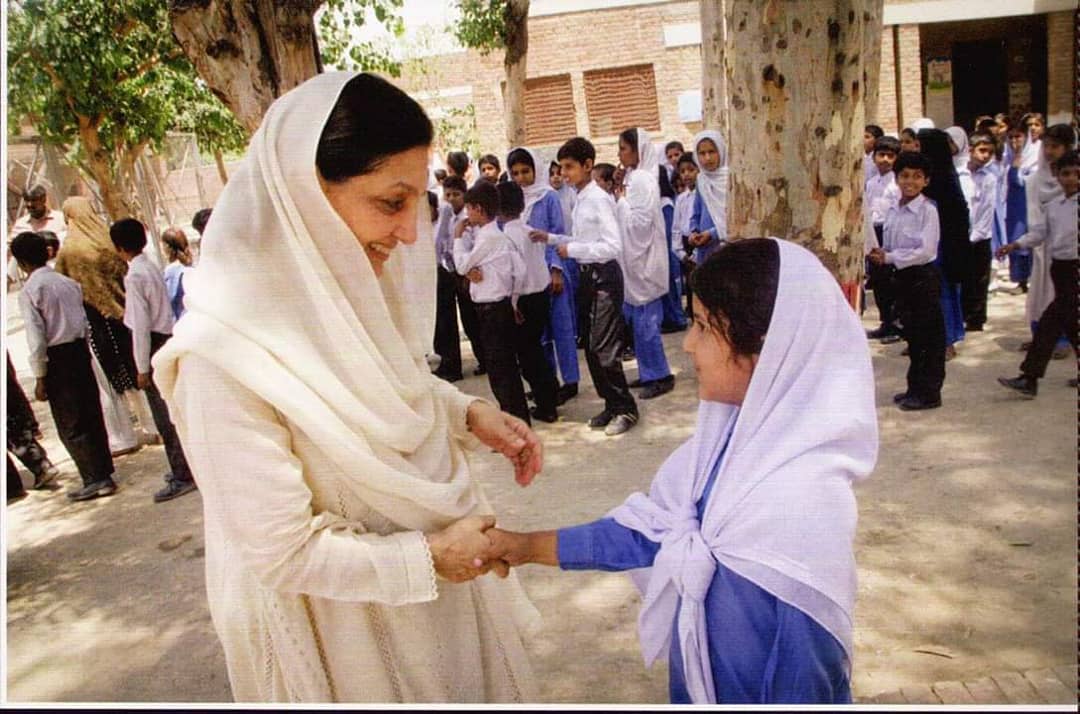

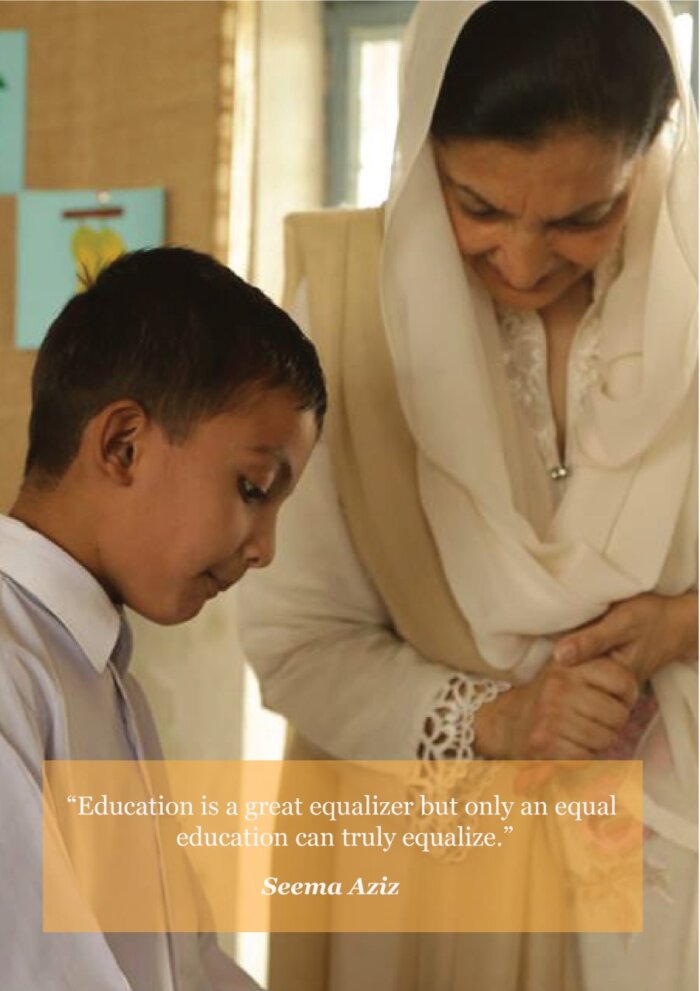

Seema Aziz (Pakistan)

Title

Founder

Organization

CARE Foundation

Country

Pakistan

Seema Aziz is the co-founder and managing director of textile company Sefam. In 1988 she founded CARE Foundation to build schools and provide quality education to underprivileged children in Pakistan. From the first school built in 1991, CARE now oversees the education of 300,000 children in 888 schools across Pakistan thanks to its innovative Adopt a School program. CAPS spoke to Seema to find out what motivates her strong commitment to improving educational outcomes for Pakistan’s youth.

CAPS: Thank you for taking the time to speak with us today. Your story is a truly remarkable story, from starting a successful textile company to founding Pakistan’s largest educational NGO. Can you take us back to the beginning and share how you become involved with community development?

Seema: It started with the business. The first shop opened its doors in 1985. We worked really hard for a whole year: running around, fixing the quality of the fabric and dyes. We put together whatever little bits of money we had and put all of our energy into the business. Soon we built a reputation for our locally made, high-quality fabrics.

The belief that we, as humans, have a responsibility to others as part of civil society was always a part of our company’s values. In 1988 there was a terrible flood in Lahore and we realized we had to help the people affected. So we went out to deliver food and medicine.

After the water receded, many people had lost their homes and there were thousands camped out on the roads. And much more help was needed. Our first idea was to help people to rebuild homes. We thought we could do ten homes. We picked ten people at random from the hundreds who applied and gave them the money to rebuild. Then we repeated the process a few times and ended up building about 80 homes.

CAPS: How did that evolve into a focus on education?

Seema: I was particularly involved in one area that was hit badly: no electricity, no sewage system and no running water. As I was going around to check on people, hundreds of children would follow me. I asked some of the women there why they were following me and they replied, “What else should they do? There’s no school.” That really horrified me. I said to them, “What if I build a school?” They were all so excited. They told me to stop building the homes and to build the school.

My friends and family in the city told me I was totally mad, that the poor don’t want to educate their children. But when I looked at the people I was trying to help, I realized the only difference between them and me was an education. Thanks to my education I had so many opportunities. Those mothers wanted a better life for their children the same as any mothers do. If the opportunity does not exist, it’s not their fault, it’s the fault of society. I decided to build a school. We collected donations from friends and family and in 1991, we opened the doors. On the day of opening 250 children were standing outside. They had all lined up for a chance at a better life.

CAPS: Apart from the physical buildings, what else went into developing the schools?

Seema: Developing the curriculum was important. When I looked at what the government schools were teaching, I realized that it wasn’t enough. That’s why we introduced the English curriculum. And we also had to provide pencils and books and other necessary supplies for the children.

I didn’t want any child to ever grow up thinking that the support we were giving them was charity, because it wasn’t. It’s their right and our duty to ensure that they get that education. And so, they each paid ten rupees for their education, then everything else was free.

By the end of the first year, word had gotten around that ours was a school where education happens. The next year we had 450 children, then 850 the year after. We acquired some more land, so we built another school and then another. And the children worked so hard, they learned everything we taught them.

CAPS: How did the partnership with the government come about?

Seema: By 1998, I was realizing the sheer number of children in need. And in my heart, I knew that only government could provide education for all. No private organization could ever provide education for all, it needed government infrastructure. That same year, the government asked me to go and survey about 25 schools in Lahore. I was horrified: no running water, no toilets, no lights, no furniture, no teachers, and children sitting on broken floors in their neat little uniforms waiting for an education, which was never going to happen. I saw in my city of Lahore, which we think of as the cultural heart of Pakistan, schools with no roofs, schools with no door.

I told the government that we would partner with them to support ten schools. CARE would take on complete responsibility for the school’s operations and expenses (capital and running), including the infrastructural improvements, staff recruitment, training and salary. We adopted government schools that were not in good shape, and by the end of the year we turned them around. Enrolments doubled and then quadrupled.

CAPS: What have been the major challenges CARE has faced?

Seema: Originally when we took over the government schools, we said that we would stay for ten years. We would help train others, then slowly reduce the number of our people. But it hasn’t worked out like that. We still haven’t exited those schools because we know the moment we walk out, they’ll collapse. They keep asking us to take on more schools, but getting money from the government has also been difficult. So, I’ve committed a percentage of my company’s earnings to CARE.

Another challenge is the drop-out rate, especially among girls. There are many bright students who do not have the means to go to college. So, we set up a scholarship program that supports our students to go to some of the best colleges in the country.

CAPS: What keeps you motivated to keep CARE running despite these challenges?

Seema: We are totally committed to children graduating. Education is a great equalizer. It shouldn’t just be available to rich children. We need to even the playing field and create equal opportunities. We really believe in that, and we’ve done our best. I think that’s the main thing.

Iris Liu (Taiwan)

Title

Vice President

Organization

Taiwan Mobile

Country

Taiwan

Iris Liu is the Vice President at Taiwan Mobile (TWM), the second largest telecom company in Taiwan. She joined in 2014, the year that Taiwan Mobile formed its Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) steering committee. Iris oversees sustainability, brand management, public relations, as well as the TWM Foundation. This allows her to create synergies within the company and develop multiple-win projects. Taiwan Mobile has become a pioneer of sustainability and innovation in Taiwan’s telecom sector, not only reducing environmental impact but also actively creating shared value. CAPS spoke to Iris Liu in January 2022 to understand Taiwan Mobile’s journey towards sustainability.

CAPS: Thank you, Iris, for sitting down with us. You started with Taiwan Mobile at the beginning of their sustainability journey. Can you share an important learning from the past eight years with the company?

Iris: Without a doubt, it is the importance of leaving no one behind in our Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) planning. Everyone in the company must be on the same page and recognize the same goal. We really struggled in the first two years because people didn’t know what they should do. It took many workshops to communicate with our employees and the steering committee, as well as our executives. This process helped us to get everyone on the same page.

CAPS: How has Taiwan Mobile crafted its ESG strategy and goals?

Iris: We update our strategy annually through a collaborative process with employees. Every year, we hold key workshops where around 200 executives gather to learn about the company’s ESG focus. This year the focus of the workshop is on Net Zero planning for 2050. We examine 52 KPIs for sustainability across the company and ask ourselves whether these are achievable and ambitious enough. Then at the end of the year, we review our progress and each business unit is assessed on its ESG performance. For instance, one of the KPIs I set for my team was to complete 50 hours of training, which they surpassed.

TWM also asked employees to “imagine the year 2030” when creating long-term goals, which helped shape the direction of our ESG strategy. TWM aims to reduce its footprint and be a responsible business. Overall, we emphasized staff working together to reach goals, and routinely updated them to respond to the changing world. Along the way, we offer many educational classes, movies related to ESG, and training support for our employees to integrate sustainability into their thinking and work.

CAPS: Who provides these workshops and classes? And when your team needs support, who can you turn to?

Iris: Since sustainability is integrated into our employees’ daily work and responsibilities, a lot of the classes are delivered internally by Human Resources. We also offer online training. In fact, during Covid-19, this option made it easier for our employees to participate because they could choose their preferred time and select what they wanted to learn. We also have an external consultant, KPMG, and we consider their advice when creating projects. And, luckily, our team always has strong support from other business units like Technical Group, Information and Technology Group, Customer Business Group etc. that give us all the resources we needed in every different projects. Most important and strongest support is from our president, our chairman, and the Board.

CAPS: Can you tell us about some of the projects that you’ve been doing as a result of this work?

Iris: Yes, for example Solar for Good. Sunnyfounder, a social enterprise, helps people develop solar energy projects in Taiwan. Sunnyfounder identifies non-profit organizations (NPOs) with available rooftop space where solar panels can be built. Sunnyfounder then attracts investments to build the infrastructure, and the energy generated by the solar panels can either be used by the NPO or sold to generate income

When I heard about this project I was immediately excited as we had a previous campaign where NT$2 from the sale of any device through Taiwan Mobile’s channels went towards developing green power and I wanted to create greater synergy by merging the two concepts. We could use the technical knowledge from Sunnyfounder to build solar panels on NPOs’ rooftops. TWM would donate one million NTD on each project and help raise money to support more NPOs to install solar panels. We named this project as “Solar for Good”.

We started “Solar for Good” since 2017, help 5 NPOs raised over NTD 24 million to build up the solar energy systems and generate over 1.4m kWh of green electricity, with more than NTD 8 million revenue accumulated till now for those five NPOs. In 20 years, the estimated total revenue for those five NPOs will be around NTD 63.21 million and approximately 9.36 million kWh of green electricity will be generated, equivalent to carbon reduction of 4907 tons of CO2e. That means that we guarantee a 20-years stable income for those NPOs and also benefit our planet with more clean energy at the same time.

CAPS: You’re creating a win-win-win for the NPOs, the community, and the environment. That is wonderful.

Iris: Thank you. For us, the win-win-win is very important. Not only are we helping to boost renewable energy, we are also helping NPOs. We also saw invisible benefits. The solar panels on the rooftops lowered the temperature of the whole building by 3-4 degrees, and so the energy consumed by the NPOs was also reduced.

CAPS: We also heard about your fiber optics project, can you tell us a bit more about that?

Iris: Three years ago we started the Circular Economy Forum. At the time, our performance on circular economy and waste management was not good enough, so we wanted to force ourselves to be better. We co-worked with KPMG and host the first forum, made a declaration with our suppliers that we would become more circular. In the second year, we consulted with our technical group to see what kind of waste we were producing and try to figure out the item that we can start our efforts with. They noted that we produced a lot of waste fiber optic cables (FOC) and identified a company, Miniwiz, researching to reduce waste. We now work with Miniwiz as well as Chang Gung University to identify how fiber optic waste cables can be turned into new products.

In a follow-up interview with Arthur Huang, CEO of Miniwiz, in February 2022, CAPS learned that as a result of this project collaboration, Miniwiz developed the technology to take FOC waste and turn it into brick and rebar substitutes. Instead of sourcing steel for construction projects, for example, a builder might source FOC “rebar” instead, which is stronger and more water-resistant than steel.

CAPS: What has been the most rewarding part of being part of TWM’s sustainability journey?

Iris: The change in people. In our steering committee, I can see that each executive is really trying to learn more about sustainability: recognizing the issue of climate change, methods used to reduce carbon emissions, and so on. But this change was not limited to the executive team, the employees also changed. In less than 3 years we have seen employees really becoming interested in integrating ESG in their work. So, I would say the biggest achievement is that we set our goals and did it together.

Operational Funding: Why it matters now more than ever

The importance of operational funding for the growth and development of Hong Kong’s social sector cannot be overstated. While social delivery organizations (SDOs) need to ensure transparency and accountability in how funding is spent, funders must consider the needs of the SDOs they are supporting, beyond project funding alone.

Operational funding allows funders to support the overall mission and vision of the SDO by helping cover the crucial costs associated with keeping an organization going, including overheads, staff salaries and training, technology upgrades, facilities, and other administrative expenses. Operational funding also provides SDOs with stability and flexibility and allows them to plan for the future.

This report identifies the demands and flows of operational support for SDOs in Hong Kong. Findings reveal the essential role of operational funding in ensuring the health and wellbeing of Hong Kong’s social sector.

Bridging the Talent Gap: A Study on Talent Development in the Philanthropy and Non-Profit Sector

This report shines a spotlight on the talent deficit in philanthropy and social sector leadership in Asia. The dearth in talent can limit the ability of the sector to grow when there is insufficient leadership behind it. Recommendations for how challenges in recruitment, integration and retention of talent can be mitigated are discussed. The report draws from 20 interviews conducted in five Southeast Asian countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. Read it here.

Ernesto Garilao (Philippines)

Title

Chairperson and President

Organization

Zuellig Family Foundation

Country

Philippines

In 1992, the Philippines devolved the provision of health services to the provincial, municipal, and city levels. This partition of public health across three different levels of government eventually created fragmentation in the overall management of the health system. The quality of basic health services generally deteriorated, and accessibility varied considerably across the country.

The Zuellig Family Foundation was established in 2008 with the ultimate vision to be “a catalyst for the achievement of better health outcomes for all Filipinos”. The foundation focuses on improving health outcomes through enabling stronger health leadership and governance in partnership with key stakeholders. CAPS sat down (virtually) with the foundation’s Chairperson and President, Ernesto Garilao, in October 2020 to understand the genesis and success factors of their Health and Leadership Transformation Program, as well as the intricacies of working with government to scale such a program across the Philippines.

CAPS: Ernesto, thank you for taking the time to speak with us today. Why did the Zuellig Family Foundation decide to focus on health leadership and governance? Why not just step in and deliver health services directly?

Ernesto: To help improve the health system in the Philippines, we looked at the six building blocks delineated by WHO (World Health Organization): leadership and governance, financing, access to essential medicines, health workforce, health information systems and service delivery. We agreed that essentially it is local leadership that moves the system—they enable the other building blocks.

And since our mission is to improve the health indicators of the most disadvantaged—and in the Philippines the health system is devolved to the local level—then it was logical and necessary to work with local government units. If we really want to address the poor, we had no alternative but to work with local governments, because the poor go to their health services.

You’re right that the alternative would be to set up the health services ourselves, but that would not be sustainable because we, as a foundation, cannot be in these towns forever. So our approach was to work with local government units on health leadership and governance.

CAPS: What are the advantages and disadvantages of working with local government units compared to the central government?

Ernesto: Well, there is less political change at the local level. The Minister of Health serves at the pleasure of the president. Mayors, on the other hand, serve three-year terms and can be reelected thrice, often serving for nine years which is a fairly long time. On the flip side, working with local government units is also a long-term time Investment and I would guess not too many foundations would like to make that time investment.

CAPS: So the mayors are the main beneficiaries of this program?

Ernesto: Yes, the mayors and their municipal health officers, and eventually their constituents. Our health change model trains local mayors to reform their health systems to provide better health services to their constituents, especially the disadvantaged. This, in turn, improves the health indicators for their areas, creating a win-win all around.

CAPS: How did you decide to use this health change model?

Ernesto: When I was at AIM (Asia Institute of Management), I developed the bridging leadership framework with my faculty colleagues. When I joined the Zuellig Family Foundation, we used this leadership framework in our ZFF health change model. The linchpin of this model is the personal transformation of the political leader into a bridging leader.

As an elected official, he must own—that’s the catchword here—must own the health inequities in his town. In other words, these poor indicators happened during his watch, so therefore he has to do something about them, right?

So if a mayor wants to improve his public health indicators, he must transform into a local health champion. This is important because he controls the delivery of primary health care, health policies, and the overall budget for his town. He has the power to improve his health services by prioritizing health in the budget.

Through our pilot from 2009-15, we demonstrated that in two to three years this leadership and governance intervention successfully lowered maternal deaths in these towns.

CAPS: And why specifically were you focusing on maternal health, rather than nutrition or other health indicators?

Ernesto: Because initially you need to have a focus, and in 2008 the Philippines’ high maternal mortality rate was a big issue. This doesn’t mean that these mayors are not offering other health services. In fact, our training was focused on general health. But the indicators we measured success by was maternal mortality. That’s because if we start saying that there must be improved maternal and child-care indicators and improved infectious diseases indicators and better non-communicable disease indicators, mayors will get overwhelmed and may not want to participate.

CAPS: Eventually the central government took notice of your program. What happened next?

Ernesto: Yes, the reduction of maternal mortality got the attention of the Minister of Health in 2013. And he said, “I like what you’re doing”. I’ve seen the program many times and I’ve watched the indicators go down. So he asked us to scale this program, essentially bringing it to the poorest municipalities with the worst health indicators across the country.

CAPS: Was the Zuellig Family Foundation excited about this opportunity?

Ernesto: Well, yes and no. We recognized that this is a great opportunity because as a foundation we always wanted to offer a product that could be mainstreamed by bigger institutions. We’re interested in developing a product, an approach, or a model that can be scaled up. And when you want to scale up, you’re really looking at government.

We recognized that we had a good program, and that if it could be scaled up it fulfils our mission of being a catalyst in improving health indicators of the disadvantaged. So we saw the central government’s interest as an opportunity, especially because growing any program nationwide requires champions inside the central government.

But we also recognized there were risks, and thought about how we could mitigate them.

CAPS: And what were some of these risks?

Ernesto: Well, for one, working with the central government means working with political appointees with no fixed terms. And priorities can change from one person to another. The political aspect is always a risk.

Secondly, even with the Minister of Health championing our intervention, it would be viewed as an “outsider” program, and not necessarily trusted by internal bureaucracy. They would have to be won over.

We went through this calculus, recognizing this as an opportunity but also being aware of these risks. The question was, how do we mitigate these risks? We decided that the program had to be co-owned between us and the Department of Health. So there was nothing in the program that did not have the approval or the consent of the Ministry of Health. They, too, had to be co-champions of the program.

CAPS: The remit you were given was massive, covering all municipalities. How did you manage it?

Ernesto: Yes, we were asked to scale it out across all municipalities. But we knew we did not have the capacity to do that—we are nowhere as big as government. So we decided to enlist and transfer the bridging leadership approach and training technology to regional academic universities and colleges. They in turn trained the mayors and health leaders of participating municipalities with funding from the Ministry of Health.

CAPS: What is the status of the program right now?

Ernesto: The program has been institutionalized. Some regional units in the Ministry of Health have taken ownership, and the Department of Health central office is now more active in pushing health leadership and governance at the federal level. All in all, the more important thing is that there is recognition that health leadership and governance is an important intervention in public health.

Why is this important? For one, because universal health care is now led at the provincial level, which means local leadership and governors will be a major factor. Number two, we have Covid-19. The response of local government units is a crucial factor on how well the pandemic is controlled. And we cannot talk about health in the age of pandemics without talking about leadership and governance. Health leadership and governance needs to be at the forefront, and the Zuellig Family Foundation has helped lay the foundation of this movement.

CAPS: You didn’t just plant the seed, you nurtured it into a tree! It’s really quite remarkable. What comes next?

Ernesto: We have become known for improving the health indicators of the disadvantaged in the Philippines, and we’ll continue working along these lines. Now we’re looking to focus on improving the health indicators of the disadvantaged faster.

Around 40% of towns in the Philippines have been exposed to our health change model, and in a sense that’s our catchment. And we will return to this catchment, to these towns, and continue to help them improve their local health systems and reduce malnutrition wasting and stunting, and adolescent pregnancies. It would be a waste not to build upon the social capital we have with these local governments.

We also look at ourselves as a catalyst who wants to leverage working with other partners to magnify impact. And make the impact long lasting. That has been our strategy from the very start: have an intervention that can be scaled up so the spillover effects are much, much greater. We plan to continue with this approach to serve the Philippines and its people.

Overview of Charity Governance in Singapore

An Overview of Charity Governance in Singapore (2017)

Good governance is critical for charities to maintain integrity in the social service industry. It is important for charities to be well governed, transparent and accountable to their stakeholders. Read it here.

Overview of Charity Sector in Singapore (2007–2013)

This study maps Singapore’s charitable sector using annual reports published between 2007 to 2013 by the Commissioner of Charities. It describes the size of the sector and its financial health, as well as trends in the type of funding received by organization and by subsector. It also raises questions on fundraising strategies, the relationship between donations and economic conditions, and grants leading to ‘crowding-in’ or ‘crowding-out’ of other forms of funding. Read it here.

Webinar: Asia Society Hong Kong Center Program Charting the Path Forward

Catching the world unaware, Covid-19 has sent the global economy and the lives of billions into a tailspin. In the wake of this pandemic, the public, private, and social sectors must come together to work towards a stronger and more equitable Asia as we build our way out of this crisis. At a time when foreign funding is declining across the region, “Asia for Asia” philanthropy must fill the gap—and the Doing Good Index shows how.

CAPS’ Co-Founder and Chief Executive Ruth Shapiro and Director of Research Mehvesh Mumtaz Ahmed present the key findings of the index and showcase how governments, philanthropists, companies and the social sector can work together for mutual benefit. This discussion was moderated by Ronnie C. Chan, Co-Founder and Chairman of CAPS and Chairman of Asia Society Hong Kong Center.

Learning Communities in Asia

What is a Learning Community? It is a group of stakeholders which may include funders, grantees and related government agencies committed to learning from success as well as failure in order to improve impact around a particular issue or challenge. A successful learning community takes collaboration to a different level. CAPS’ latest report, Learning Communities in Asia: Doing Good Together, shares findings on which factors contribute to vibrant and sustainable learning communities within the Asian context.

Advocacy, Rights & Civil Society: The Opportunity for Indian Philanthropy

This report examines the changing trends in nonprofit funding in India. Restrictions on the flow of foreign funding and its impact on Indian civil society organizations receive special attention. Opportunities for Indian philanthropists to play a more enabling role in this changing landscape are also discussed.

The Doing Good Index 2018 by CAPS found that several Asian economies are regulating receipt of foreign funding including Pakistan, China, Indonesia, and Vietnam. As regulations on foreign funds seem to be on the rise across Asia, this report serves as valuable insight on the consequences. Read it here.